Complex Numbers

In this comprehensive tutorial you will learn:

- The nature of a complex number

- Complex Conjugate

- Addition, subtraction, multiplication and division of complex numbers

- Finding complex roots of equations

- Argument and modulus of complex numbers

- Polar form of a complex number

- Locus of points on Argand Diagram

- Euler's relation - complex number in the exponential form

- de Moivre's Theorem

- Trigonometric Identities by de Moivre's Theorem

E.g.1

As with everything in maths, complex numbers

also have its own birth, may be even in multiple forms! This is one form of

it.

Suppose we want to solve the quadratic

equation, x2+ x + 6 = 0. If we

stick to the formula method, the process is as follows:

x = [-1 + √(1 - 24)]/2 or x

= [-1 - √(1 - 24)]/2

x = [-1 + √( - 23)]/2 or x

= [-1 - √(- 23)]/2

We cannot go beyond this point, as we

have come to a stage where we have a square root of a negative number; we have

been told it does not exist and we wind up our calculation with familiar

conclusions - there are no real roots or solutions. That's it.

However, that was not the end of the

world for mathematicians; they have gone much further than that and the concept

of complex numbers was born.

In the above example we came across

√(-23). Using the rules on indices, we can write it as follows:

√ -23 = √ -1 √ 23

Now we call √-1 as i, and suddenly √-23

becomes something that can be handled.

√-23 = i√ 23

Now, the above quadratic equation can be

solved!

x = (-1 + i√23)/2 or (-1 - i√23)/2

Solutions are expressed in terms of i.

These are called complex numbers.

Complex numbers are expressed in terms of

i or √-1.

- i = √-1

- i2 = √-1.√-1 = -1

- i3 =

√-1.√-1.√-1 = -i

- i4 =

√-1.√-1.√-1.√-1 = -1 x -1 = 1

The Form of a Complex Number

Z = a + ib

a = the real part of the complex number

ib = imaginary part of the complex number

i = √-1

A complex number can be

represented in a x-y grid. Then it is called an Argand Diagram: the real part is

shown in the x-axis and the imaginary part in the y-axis.

This is the Cartesian representation of a complex

number: the x-axis represents the real part; y-axis represents the imaginary part.

Complex numbers can be

added, subtracted, multiplied and even divided like any other number, with a bit

of caution though.

E.g.

Z1 = 8 + i6 ; Z2 = 2 - i4

Addition

Z1 +

Z2 = (8 + 2) + i (6 - 4) = 10 + i2

Subtraction

Z1 -

Z2 = (8 - 2) + i (6 - -4) = 6 + i10

You can practise addition and subtraction interactively with the following applet. Move Z1 and Z2 so that Z3 and Z4 represent addition and subtraction respectively.

Multiplication

Z1.Z2

= (8+i6).(2-i4)

= (8X2) - (8X4i) +

(2X6i) - 24i2

= 16 - i32 + i12 -

24(-1) ; note i2 = -1

= 16 -i20 +

24

= 40 - i20

Complex Conjugate - Z*

If a + bi is a complex number, a - bi is called its complex conjugate.

E.g.

Z = 2 - 3i, so Z* = 2 + 3i

Z = 2 + 3i, so Z* = 2 - 3i

Z = -2 - 3i, so Z* = -2 + 3i

Division

Z1 / Z2

= (8 + i6) / (2 - i4)

In this case, we need a special way of dealing with the division;

Multiply both the top

and the bottom by the complex conjugate of the bottom. That's it.

Z1 / Z2

= (8 + i6) * (2 + i4) / [(2 - i4)(2 + i4)]

= (16 + i32 + i12

+ i224) / (4 + i8 - i8 - i216)

= (-8 + i44) /

(20)

= -2/5 +

i(11/5)

You can practise multiplication and division interactively with the following applet. Move Z1 and Z2 so that Z3 and Z4 represent multiplication and division respectively.

Finding the square root of a complex number

Find the square root of 8 + 6i

Let (a + bi)2 = 8 + 6i, where a + bi is the square root of 8 + 6i.

So, a2 + 2abi - b2 = 8 + 6i

Making the real parts on both sides equal,

a2 - b2 = 8

Making the coefficients of i on both sides equal,

2ab = 6 => b = 6/2a = 3/a

Sub in the other,

a2 - 9/a2 = 8

a4 - 9 = 8a2

a4 -8a2 -9 = 0

Let y = a2

So, y2 -8y -9 = 0

(y - 9)(y + 1)

y = 9 or y = -1 => a2 = 9 or a2 = -1

Since a2 = -1 not valid, a2 = 9 => a = ± 3

Sub in b = 3/a => b = 1 or b = -1

So, the square roots of 8 + 6i = (3 + i) or (-3 -i)

The modulus of a complex number - |Z|

The length of the vector that represents the complex number is called its modulus.

If z = a + ib, then modulus is defined as,

√(a2 + b2)

|Z| =√(a2 + b2)

The argument of a complex number - arg z

The angle between the positive real axis and the vector that represents the complex number is the argument of the complex number.

If arg z = θ, -180 < θ <= 180 or -π < θ <= π

You can practise the concepts with the following animation. Please move the point, Z1 with your mouse and see the changes.

Have you noticed how the arg z, changes? It can only take values between -1800 and 1800 - or its radian equivalents.

Solving Polynomial Equations

If a polynomial equation - quadratic or higher - has complex roots, they are in the form of conjugate pairs - a ± b. Sometimes, one or many be real roots as well - a ±0i.

E.g.1

Solve x3 - 6x2 + 21x - 26 = 0

f(x) = 0

f(2) = 0 => from factor theorem, x-2 is a factor.

Divide x3 - 6x2 + 21x - 26 by (x-2)

You get, x2 - 14x + 13 with no remainder.

Solve, x2 - 14x + 13 = 0

x = 2 ± 3i

So, the roots are x =2, x = 2 ± 3i

You can see that there is one real root and two complex roots for the equation - in complex conjugate form.

You can use the following applet to solve polynomials. Just type in the equation in the text box and click the button. Make sure you use, ^, to represent the powers of x. Use arrow keys, rather than the mouse, while typing in the equations. All roots appear with, Z. If they are not visible, just move the grid and look for them!

The Locus of points on an Argand Diagram

Complex numbers can be used to find the locus of points on an Argand diagram.

E.g.1

The locus of a point, Z, which keeps the distance between it and a fixed point, Z1 , the same is a circle.

In the example, |Z - Z1| = 3; it means the locus of the point in question is a circle of radius 3, with the centre at Z1.

In order to animate it and see it in action, please press the play button.

|Z - Z

1| = 3

|Z - (5 + 4i)| = 3

|Z - 5 - 4i)| = 3

This is a circle with centre, (5,4) and radius = 3.

So, the equation of the locus - the circle in this case - is (x - 5)

2 + (y - 4)

2 = 3

2.

E.g.2

The locus of a point, Z, which keeps the distance between two fixed points, Z1 and Z2, the same is the perpendicular bisector of the line between the two points.

In the example, the point, Z, moves while keeping the distances between the points, Z1 and Z2, the same; it means the locus of the point in question is the perpendicular bisector of the line that joins Z1 and Z2.

In order to animate it and see it in action, please press the play button.

You can move the point, Z, in order to see that it lies on the perpendicular bisector.

Since it is a straight line, the equation of the locus takes y = mx + c form.

Please move the point, Z1, to see how the equation of the locus changes. You can use it as an exercise to find the equation of the locus.

The polar representation of a complex number - modulus argument form

Here, the angle t in radians is called the argument. Therefore, the complex number can be written in

terms of its modulus and the argument. This is called the polar

representation of the complex number

a = |Z| cos θ : b = |Z| sin t : θ = tan

-1(b/a) ; -π< θ <= π

Z = |Z| cos θ + i|Z| sin θ

If the modulus of a complex number is r and the

argument is t, it can be written as (r,θ) in the polar form.

E.g.1

Write the complex number, Z = 3 + i4

in the polar form.

|Z| = √(32 + 42) = 5

t = tan

-1(4/3) = 0.92

Z = (5,0.92).

E.g.2

Write Z = (10,0.3) in Cartesian

form.

a = 10 cos 0.3 = 9.5

b= 10 sin 0.3 = 2.9

Z = 9.5 + i2.9

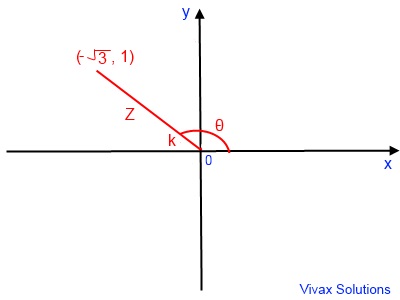

E.g.3

If Z = -√3 + i, write it in the form of r(cos θ + i sin θ).

tan k = 1/√3

k = π/6

θ = π - k = 5π/6

|Z| = √(3 + 1) = 2

Z = 2(cos 5π/6 + i sin 5π/6)

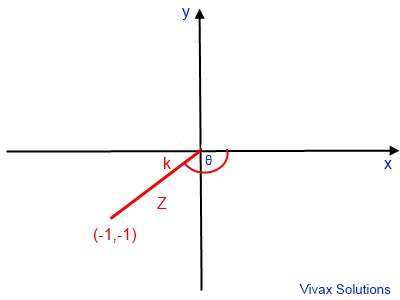

E.g.4

If Z = -1 - i, write it in the form of r(cos θ + i sin θ).

tan k = -1/-1 = 1

k = π/4

θ = π + k or -(π - k);

Since -π< θ <=π

θ = -(π - π/4) = -3π/4

|Z| = √(1 + 1) = √2

Z = √2(cos -3π/4 + i sin -3π/4)

Maclaurin Series

f(x) = f(0) + f'(0)x/1! + f"(0)x2/2! + f"'(0)x3/3! + ....

sin(x) = sin(0) + cos(0)x/1! + -sin(0)x2/2! - cos(0)x3/3! + ...

= x -x3/3! + x5/5!

cos(x) = cos(0) - sin(0)x/1! - cos(0)x2/2! + sin(0)x3/3! + ...

= 1 -x2/3! + x4/4!

ex = 1 + e0x/1! + e0x2/2! + e0x3x/3!+...

= 1 + x + x2/2! + x3/3! + ...

Complex Numbers in Exponential Forms - Euler's Relation

From Maclaurin Series,

eiθ = 1 + iθ/1! + (iθ)2/2! + (iθ)3/3! + ...

= 1 + iθ - θ2 -iθ3/3! + θ4/4! + iθ5/5! - θ6/6!

= (1 - θ2 + θ4/4! - θ6/6!... ) + i(iθ -iθ3/3! + iθ5/5!...)

= cos θ + i sin θ

eiθ = cos θ + i sin θ

Z = r[cos θ + i sin θ ]

Z= reiθ

E.g.1

Express Z = √3 + i in the form of Z = reiθ

r = √(3 + 1) = 2

tan θ = 1/√3 => θ = π/6

Z = e

iπ/6

E.g.2

Express Z = 3 cos π/3 + i sin π/3 in the form of Z = eiθ.

r = 3; θ=π/3

Z = 3e

iπ/3

E.g.3

Express Z = 5 cos π/4 - i sin π/4 in the form of Z = eiθ.

Z = 5 cos (-π/4) + i sin (-π/4), because cos(-x) = cos(x) and sin(-x) = -sin(x)

r = 3; and θ=-π/4

Z = 3e

-iπ/4

E.g.4

Express Z = 4ei5π/4 in the form of Z = r[cos θ + i sinθ].

Since -π< θ <=π, θ = -π/4; r = 4

So, Z = 2[cos -π/4 + i sin -π/4]

Product and Division of Complex Numbers

Let Z1 = r1[cosθ1; + i sinθ1;] = eiθ1; ;

Z2 = r2[cosθ2; + i sinθ2;] = eiθ2;

Z1 X Z2 = r1eiθ2; X r2eiθ2;

= r1r2ei[θ1 + θ2]

= r1r2[cos(θ1 + θ1) + i sin(θ1 + θ2)]

Z1 / Z2 = r1eiθ2; / r2eiθ2;

= (r1/r2) ei[θ1 - θ2]

= (r1/r2) [cos(θ1 - θ1) + i sin(θ1 - θ2)]

Based on the above proofs, the following set of rules applies in dealing with the product and division of complex numbers:

|Z1 Z2 | = |Z1||Z1|

arg(Z1Z2) = arg(Z1) + arg(Z2)

|Z1 / Z2 | = |Z1|/|Z1|

arg(Z1 / Z2) = arg(Z1) - arg(Z2)

E.g.1

Express 2(cosπ/6 + i sinπ/6) X 3(cosπ/6 + i sinπ/6)in the form of x + iy.

= 6(cos(π/6+π/6) + i sin(π/6+π/6)

= 6(cosπ/3 + i sinπ/3)

= 3 + 3√3i

E.g.2

Express 12(cos5π/6 + i sin5π/6) / 3(cos2π/6 + i sin2π/6)in the form of x + iy.

= 4(cos(5π/6-2π/6) + i sin(5π/6-2π/6)

= 4(cos3π/6 + i sin3π/6)

= 4(cosπ/2 + i sinπ/2)

= 4(0 + i)

= 4i

E.g.3

Express 5(cos5π/6 + i sin5π/6) X 2(cos2π/6 - i sin2π/6)in the form of x + iy.

= 5(cos5π/6 + i sin5π/6) X 2(cos(-2π/6) + i sin(-2π/6)) , because, cos-θ = cosθ and sin-θ = -sinθ

= 10(cos3π/6 + i sin3π/6)

= 10(cosπ/2 + i sinπ/2)

= 10(0 + 1i)

= 10i

de Moivre's Theorem

[r(cosθ + isinθ)]n = rn[cos nθ + i sin nθ]

de Moivre Theorem in exponential form

Z = r[cosθ + isinθ]

Z

n = r

n[cosθ + isinθ]

n

Z

n = r

n[cos nθ + isin nθ]

Z

n = r

ne

i(nθ)

The path leading to de Moivre's Theorem

By multiplying two complex numbers together, it is easy to show the path that leads to de Moivre Theorem, which is as follows:

Z = r[cosθ + i sinθ]

Z

1 = r

1[cos1θ + i sin1θ]

1

Z

2 = Z X Z = r

2[cos2θ + i sin2θ]

2

Z

3 = Z

2 X Z = r

2[cos2θ + i sin2θ] X [cos1θ + i sin1θ]

Z

3 = r

3[cos3θ + i sin3θ]

3

Z

4 = Z

3 X Z = r

3[cos3θ + i sin3θ] X [cos1θ + i sin1θ]

Z

4 = r

4[cos4θ + i sin4θ]

4

Z

5 = Z

4 X Z = r

4[cos4θ + i sin4θ] X [cos1θ + i sin1θ]

Z

5 = r

5[cos5θ + i sin5θ]

5

...

...

...

...

Z

n = r

n[cos nθ + i sin nθ]

n

This is

de Moivre's Theorem.

de Moivre's Theorem is valid for any rational number - negative and positive integers as well as fractions. Normally, it is proved by the mathematical induction method.

It is true for any positive integer, n

[r(cos θ + i sinθ)]

n = r

n[cos nθ + i sin nθ]

n=1

LHS: [r(cos θ + i sinθ)]

1 = r[cosθ + i sinθ]

RHS: r

1[(cos1θ + i sin1θ)] = r[cosθ + i sinθ]

Since

LHS: =

RHS:, de Moivre Theorem is true for n=1.

Assume that de Moivre's Theorme is true for

n=k. So,

Z

k = r

k[cos kθ + i sin kθ]

Now. let's try it for n = k+1

[r(cos θ + i sinθ)]

k+1 = [r(cosθ + i sinθ)]

k[r(cos θ + i sin θ)]

= [r

k(cos kθ + i sin kθ)][r(cosθ + i sinθ)]

= [r

k+1(cos (k+1)θ + i sin (k+1)θ)]

Therefore, if de Moivre's Theorem is true for n=k, it is true for n=k+1; Since it is true for n=1 too, de Moivre's Theorem is true for any integer, n>=1.

n=0

LHS: [r(cos θ + i sinθ)]

0 = 1

RHS: r

0[(cos0θ + i sin 0θ)] = 1[1 + 0] = 1

Since

LHS: =

RHS:, de Moivre's Theorem is true when n=0.

n is negative =>n<0

Let n=-m, where m is a positive number.

Since the theorem is true for positive integers,

LHS: [r(cos θ + i sinθ)]

n = [r(cos θ + i sinθ)]

-m

= 1 / [r(cos θ + i sinθ)]

m

= 1 / [r(cos mθ + i msinθ)] (since it is valid for positive integers)

X [cos mθ - i sin mθ] / [cos mθ - i sin mθ] =>

= [cos mθ - i sin mθ] / [(cos mθ - i sin mθ)r

m(cos mθ + i msinθ)] =>

= [cos mθ - i sin mθ] / r

m[cos

2mθ - i

2 sin

2mθ]

= [cos mθ - i sin mθ] / r

m[cos

2mθ + sin

2mθ]

= [cos mθ - i sin mθ] / r

m X 1

=r

-m[cos mθ - i sin mθ]

=r

-m[cos (-mθ) + i sin (-mθ)], since cos-θ= cosθ and sin-θ=-sinθ

Since -m = n

r

n[cos nθ) + i sin nθ]

RHS:

For fractions

Let n=p/q, where p and q are integers.

[r(cos θ + i sinθ)]

p = r

p[cos pθ + i sin pθ]

= r

p[cos pq(1/q)θ + i sin pq(1/q)θ]

= r

p[cos p(1/q)θ + i sin p(1/q)θ]

q

Now take the q

th root of both sides

=r

p/q[cos p(1/q)θ + i sin p(1/q)θ]

=r

p/q[cos (p/q)θ + i sin (p/q)θ]

= r

n[cos nθ + i sin nθ]

Therefore, deMoivre's Theorem is valid for fractions as well.

Derivation of Trigonometric Identities by de Moivre's Theorem

In order to derive the trigonometric identities, we are going to use the binomial expansion along with de Moivre Theorem.

(a + x)n = Σ nCr an-r xr

E.g.1

Find an identity for cos5θ.

[cosθ + i sinθ]5 = Σ 5Cr cosθ5-r (i sinθ)r

= cos5θ + 5 cos4θ(i sinθ) + 10 cos3θ(i sinθ)2 + 10 cos2θ(i sinθ)3 + 5 cosθ(i sinθ)4 + (i sinθ)5

= cos5θ + 5 cos4θ(i sinθ) + 10 cos3θ(-sin2θ) + 10 cos2θ(-i sin3θ) + 5 cosθ(sin4θ) + (i sin5θ)

From de Moivre't Theorem,

[cosθ + sinθ]5 = [cos5θ + i sin5θ]

So, [cos5θ + i sin5θ] = cos5θ + 5 cos4θ(i sinθ) + 10 cos3θ(-sin2θ) + 10 cos2θ(-i sin3θ) + 5 cosθ(sin4θ) + (i sin5θ)

Now equate the real parts on both sides:

cos5θ = cos5θ + 10 cos3θ(-sin2θ) + 5 cosθsin4θ

= cos5θ + 10 cos3θ(-sin2θ) + 5 cosθ(sin2θ)2

= cos5θ -10 cos3θsin2θ + 5 cosθ(1 - cos2θ)2

= cos5θ -10 cos3θ(1 - cos2θ) + 5 cosθ(1 -2cos2θ + cos4θ)

= cos5θ -10 cos3θ + 10 cos5θ + 5 cosθ -10cos3θ +5cos5θ

= 16cos5θ -20 cos3θ + 5 cosθ

cos 5θ = 16cos5θ -20 cos3θ + 5 cosθ

E.g.2

Find an identity for sin4θ.

[cosθ + i sinθ]4 = Σ 4Cr cosθ4-r (i sinθ)r

= cos4θ + 4 cos3θ(i sinθ) + 6 cos2θ(i sinθ)2 + 4 cosθ(i sinθ)3 + (i sinθ)4

= cos4θ + 4 cos3θ(i sinθ) + 6 cos2θ(-sin2θ) + 4 cosθ(-i sin3θ) + (i sin4θ)

From de Moivre't Theorem,

[cosθ + sinθ]4 = [cos4θ + i sin4θ]

So, [cos4θ + i sin4θ] = = cos4θ + 4 cos3θ(i sinθ) + 6 cos2θ(-sin2θ) + 4 cosθ(-i sin3θ) + (i sin4θ)

Now equate the imaginary parts on both sides:

sin4θ = 4cos3θsinθ - 4 cosθ sin3θ + sin4θ

sin 4θ = 4cos3θsinθ - 4 cosθ sin3θ + sin4θ